“We call this complex of patterns the third culture, and define it broadly as the behavior patterns created, shared, and learned by men of different societies who are in the process of relating their societies, or sections thereof, to each other.”1

Distinct cultures in close geographical proximity have been known to interact and war, but they also exchange and even thrive in the cultural sparks that came out of the clashing of unique cultural differences. Curiosity is universal, trumping the fear of the unknown and potential dangers, for a simple desire: to seek out new realms and elements of this world that inspires.

Then came the Age of Discovery of the early modern period, when invention of faster ship and refined navigation methods allowed surer means of sea travels, and so began a period of great expeditions all across the globe.

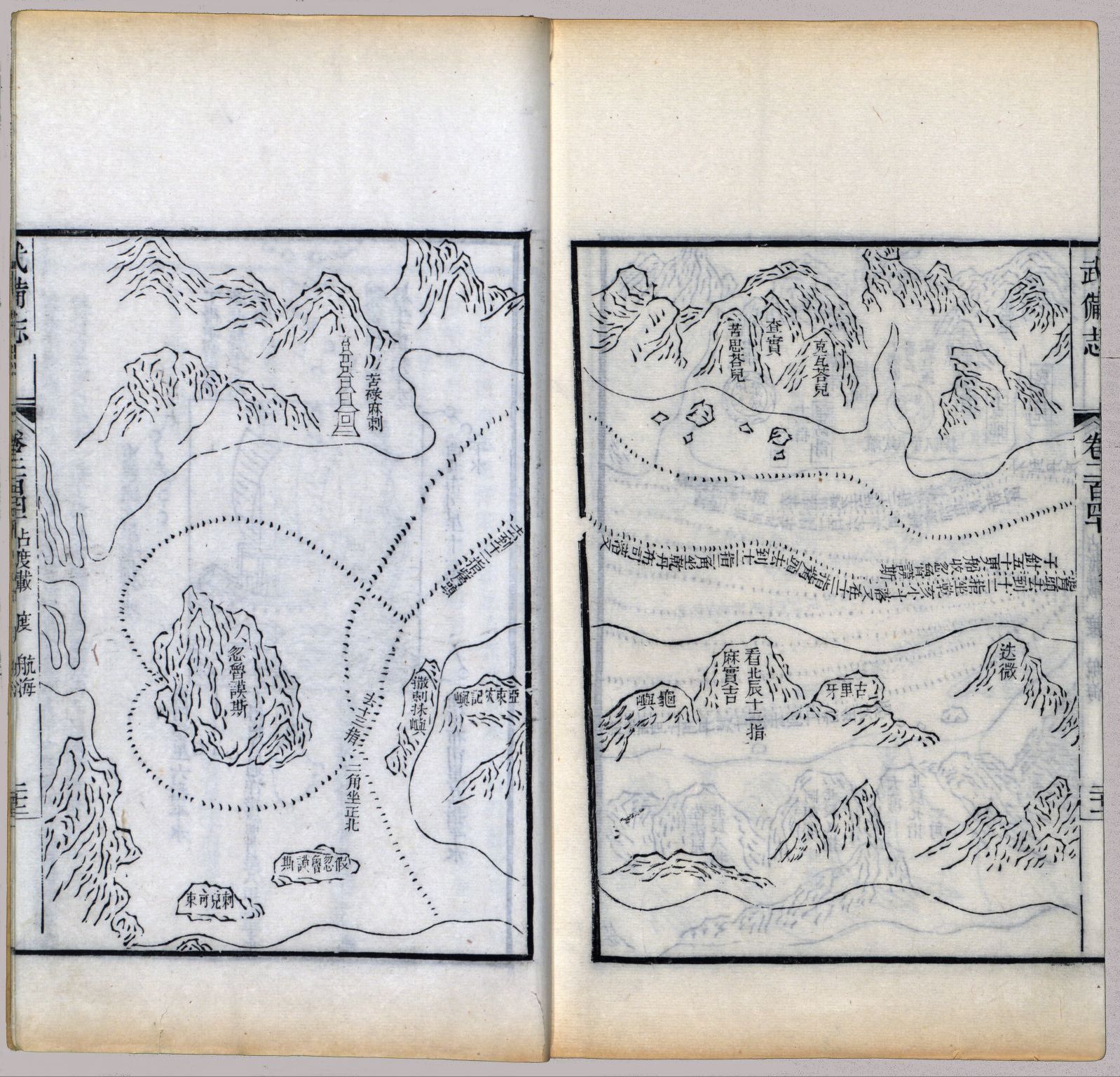

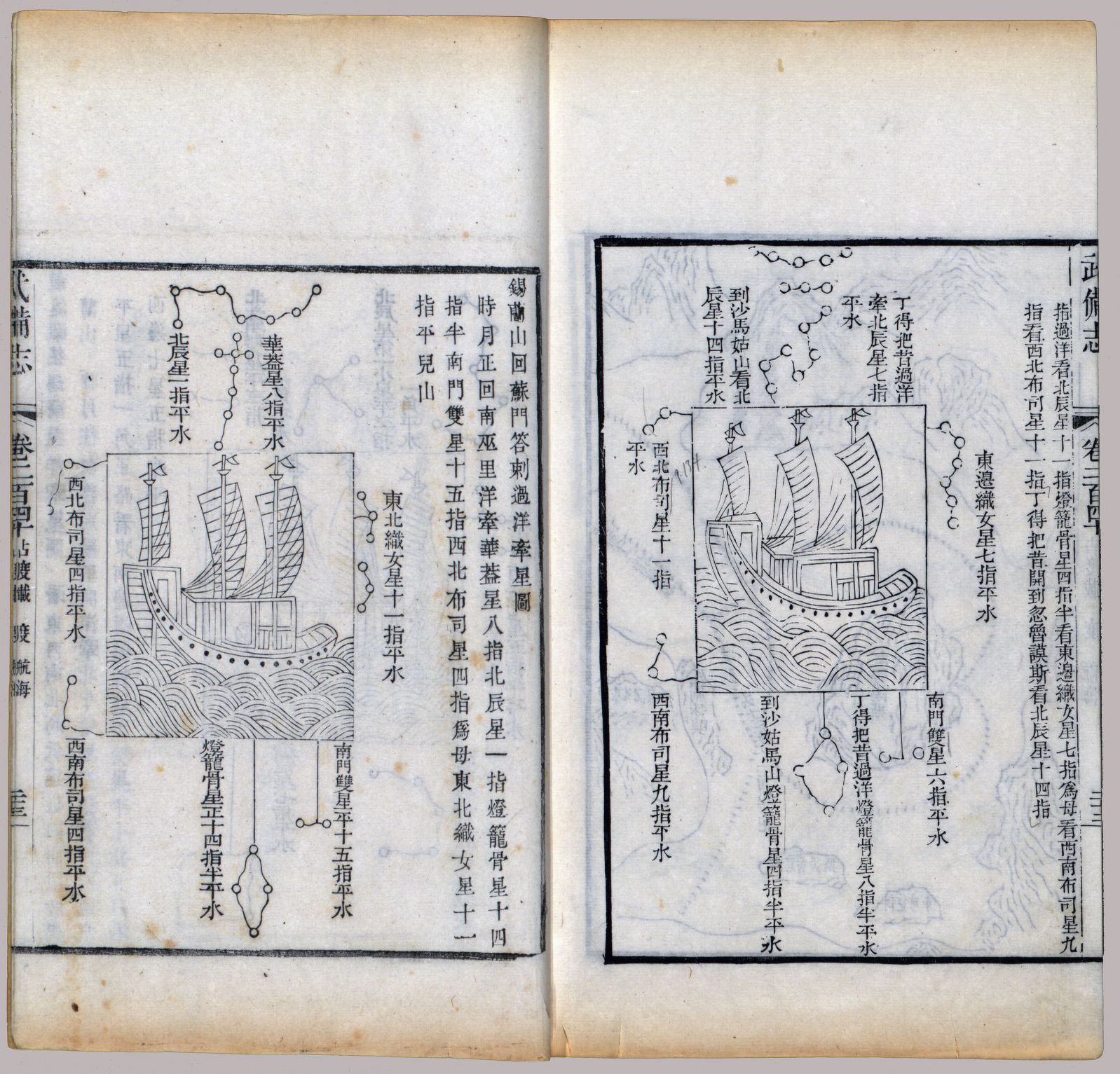

Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming Travel Voyages, led by admiral Zheng He, set out 7 times along the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, carrying as many as 25,000 crew and companions. They visited more than 30 nations and territories and reached as far as East Africa. Their mission was to learn the unknown, collect treasures and wonders, and to show the prowess of the great Ming dynasty. The great endeavor was able to be realized because of the cultural exchange with the Arabs and Indians, from whom the Ming learned ways of navigation and topography2. Such inference is evident by the “Stellar Charts” within the collection of the ‘Mau Kun Map’, which recorded Zheng He’s voyages.

Cross oceanic explorations were happening all around the globe. It was during this period that the need for localized expats arose, following efforts of colonization. The British — whose empire by colonies comprised of nearly a quarter of the world’s land surface by the end of the 19th century — for example, had nearly 20,000 overseas colonial officers, including education officers, engineers, medical officers and other functionaries3. Stations of military or diplomatic personnel and missionaries of Christianity on a foreign land, where these people found themselves in a foreign land raising their children and/or forming new families with locals. Regardless of efforts to establish a colony with their native culture, a more profound and prolonged cross-cultural mix happened. For an array of needs of keeping peace, maintaining smooth commerce, and simply for a human need of connection, these people created an inter-mingled “culture” of their own, for the purpose of survival right on the boundaries of two cultures. They were the first look of the culture makers, the third culture.

The third culture cannot be fully understood without reference to the societies it relates to and in which the participants learned how to act as humans4. These third cultures actively relate their own cultures with the locals while acclimating to the local culture, all the while keeping the agenda of maintaining exchanges and dialogues. They are men in the middle by way of the cultural patterns they create, learn and share, possessing a two-way traffic, giving insights to a notion of identity as event rather than categorical declaration that is both various and mutable.

A most beautiful example is perhaps the American born writer Gertrude Stein, whose Paris salon was the mingling ground for critical cultural figures such as Hemingway and Picasso. Stein herself devoted much of her writing over the expressing of one’s identity and the autonomy of that expression. Her American heritage and self-chosen French influence played a large part in that exploration. In her autobiographical work, Paris France, Adam Gopnik prefaced: “It is a picture of Paris by an American who thinks as Americans think, and we see America in the picture when she thinks she is showing us France.”5

A most beautiful example is perhaps the American born writer Gertrude Stein, whose Paris salon was the mingling ground for critical cultural figures such as Hemingway and Picasso. Stein herself devoted much of her writing over the expressing of one’s identity and the autonomy of that expression. Her American heritage and self-chosen French influence played a large part in that exploration. In her autobiographical work, Paris France, Adam Gopnik prefaced: “It is a picture of Paris by an American who thinks as Americans think, and we see America in the picture when she thinks she is showing us France.”5

Then there were the kids of the third culture.

“ATCKs (adult third culture kids) feel different but not isolated… are not isolated and alienated.”6

“ATCKs (adult third culture kids) feel different but not isolated… are not isolated and alienated.”6

They grew up with no stated political or cultural agenda, yet they faced cross-cultural circumstances from the very beginning. They were not the dominant culture on the ‘foreign land’, and they often didn’t even know or remember much of what their supposed “native” conducts were like except through their third culture parents. When Ruth Hill Useem first conducted her studies on what she coined as the “Third Culture Kids (TCKs)” in India, it was the 60s.

Then a wave of decolonization happened in the face of the rise of global call for democracy, and these TCKs returned “home” to find themselves facing yet another need to adjust.

“they never adjust. They adapt, they find niches, they take risks, they fail and pick themselves up again.They succeed in jobs they have created to fit their particular talents, they locate friends with whom they can share some of their interests, but they resist being encapsulated. They are loners without being particularly lonely. Their camouflaged exteriors and understated ways of presenting themselves hide rich inner lives, remarkable talents, and, often, strongly held contradictory opinions on the world at large and the world at hand.”7

So many things shifted: language, landscape, sight, sounds, people, the look of people, language, acts, customs, expectations, language, language language.

Yet as they seemed to be catching up, they also realized that they were “more.” What they have seen, done, whom they have met, spoken with, see, saw, heard, then. The first wave of third culture children had no choice but to quietly immerse themselves back into a foreign motherland, yet they did hold on to that which makes them unique.

The understanding.

“In an attempt to be even more specific about the shared lifestyle of the expatriate community, Norma McCaig (2002, p.11) coined the term ‘global nomads’ to emphasize the unique experiences of those ‘who are raised and educated internationally due to a parent’s career choice.”8

“In an attempt to be even more specific about the shared lifestyle of the expatriate community, Norma McCaig (2002, p.11) coined the term ‘global nomads’ to emphasize the unique experiences of those ‘who are raised and educated internationally due to a parent’s career choice.”8

The world has since seen more than two decades of globalization; nations have risen and nations have fallen, boundaries redrawn and the idea of nationality blurred, challenged. Rise of the third culture who freely locate themselves not always because of a patriotic mission, but often for a self-initiated career choice. This raises a whole new generation of third culture kids, the nomads.

What makes this generation unique is not only the sheer increase in volume, but also a shift in the political and cultural dynamic this world has come to accept. Never quite at the center of attention, the third culture continues to be a subject of study within a small circle of scholars across sociology and even performance studies. In her analysis, Dr. Heidi R. Bean compares the iterative style of writing of Stein to that of performative writing.

Implicitly or explicitly, the body is finally revealed as a medium both of instantiation and incorporation in performative identity9, and perhaps no one gets a complete history of anyone.

As Brockman put it in his 1991 statement: “the strength of this population is precisely that it can tolerate disagreements about which ideas are to be taken seriously; the achievements are not the marginal disputes; they will affect the lives of everybody on the planet.”10

I call them the Culture 3.0.

Pages* from Ming Dynasty book Wu Bei Zhi [武備志] (1628) (section of an ocean travel chart, believed to be based on Zheng He's expeditions.)

Pages* from Ming Dynasty book Wu Bei Zhi [武備志] (1628) (section of an ocean travel chart, believed to be based on Zheng He's expeditions.) Pages of ‘Stellar maps’*, also from Wu Bei Zhi [武備志] (1628)

Pages of ‘Stellar maps’*, also from Wu Bei Zhi [武備志] (1628)

One of the Colonial Training Courses, Devonshire Course**, Oxford, 1948/9

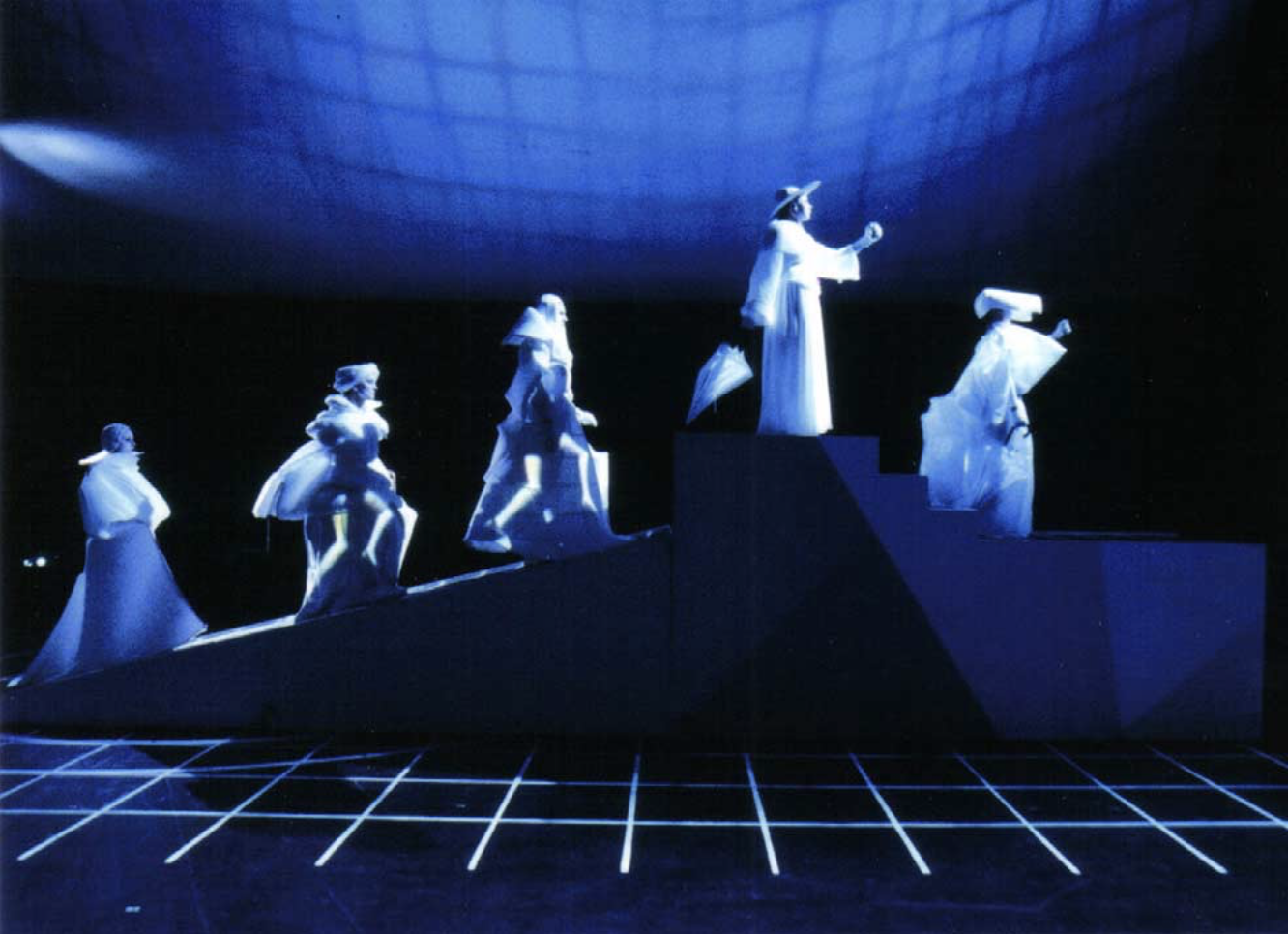

Adaptation of Stein’s “The Making of Americans” by the Gertrude Stein Repertory Theatre***

Adaptation of Stein’s “The Making of Americans” by the Gertrude Stein Repertory Theatre***1. Useems, Donoghue 1963. 169.

2.〈鄭和航海圖〉解讀, Lai 2017. www.sciencehistory.url.tw/?p=204

3. “British Colonial Expertise, Post-Colonial Careering and the Early History of International Development“ 2010. 24.

4. Useems, Donoghue 1963. 170.

5. Useem, Cottrell 1996. 27.

6. Stein 2013.

3. “British Colonial Expertise, Post-Colonial Careering and the Early History of International Development“ 2010. 24.

4. Useems, Donoghue 1963. 170.

5. Useem, Cottrell 1996. 27.

6. Stein 2013.

7. Useem, Cottrell 1996. 24.

8. Tanu 2015. 17.

9. Bean 2007. 168.

10. Brockman 1991.

* digital images from Library of Congress Asian Division Washington, D.C.9. Bean 2007. 168.

10. Brockman 1991.

** www.britishempire.co.uk/article/colonialservicetrainingcourses.htm

*** Bean 2007. 184. Photo:Reggie Morrow. (Left to right: Natalie Baldi, Melissa Arnesen-Trunzo, Kara Ewinger,Sierra Spies, and Natalie Norton.)